MIGHTY ROASTERS OF A SINGLE POUND

Building a Micro-Roasting Business

by Mark Crawford

IT’S TOUGH MAKING money roasting coffee a pound at a time, at least when you’re selling beans by the bag. It almost seems absurd to roast three 1-pound cycles an hour, four hours a day, five days a week. And not just roasting—what about selecting your green, blending and sweeping chaff from far and near? You might finish off the month with 224 pounds of coffee and a grand total of $1,500 in sales. But if your main revenue is serving your own specialty coffee drinks at retail, is it worth the effort to roast?

Maybe.

In 2005, Adam McGovern and his business partner, Aric Miller, opened Coffeehouse Northwest in Portland, Ore. After three years, they decided to scratch their itch to roast. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” McGovern explains. “We had thought about roasting for a while, and then we realized that it would improve our margins and make the [profit and loss] look better. So we set out for great coffee and great margins.”

Earlier this year, the pair debuted Sterling Coffee Roasters, a coffee cart showcasing fresh-roasted coffee from a 1-pound refurbished San Franciscan drum roaster that customers can see in action. In addition to whole bean, the cart also offers espresso, press and single-serve.

Sterling’s early sales figures surprised the owners. “We expected whole bean to be about 10 percent of our sales, and it’s actually more like 45 [percent],” McGovern says. “It’s been really astonishing. Even at our most optimistic projections, it was only around 25 percent.”

We all know that coffee tastes better when it’s been fresh roasted. And buying green coffee in small quantities is easier than it’s ever been. So it’s no wonder that businesses focusing on roasting small batches—as well as those that regularly use 1- to 2-pound roasters to fulfill smaller orders—are popping up around the country.

Whether you are just starting to roast or are considering expanding your roasting arsenal, here are a few tips from small-batch roasters to help you incorporate a single-pound roaster into your business.

1. Start small

Interested in launching a roasting business? Working with small-batch machines allows roasters to launch their businesses with small initial investments and grow their companies organically, as their markets expand.

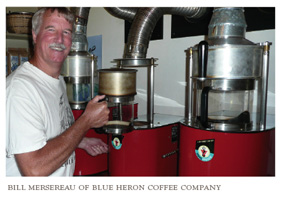

Bill Mersereau, owner of Blue Heron Coffee Company on Samish Island, Wash., began home roasting 15 years ago. He decided to turn his hobby into a part-time business in 2002, investing about $2,500 for a 1-pound Sonofresco roaster and bags for packaging. But demand soon outpaced his production, and he found himself constantly roasting. “I purchased a second [1-pound] roaster and later a third as business began to build,” Mersereau says. “With the additional roasters, I could produce more product in the short time I had. It’s a very minimal investment in terms of starting a business.”

Even for coffee-industry veterans, a small start-up with a single-pound roaster can prove to be a relaxed way to relocate a business or start a new one.

Recently, Charlotte Crawford moved from the Pacific Northwest to farmland outside Nashville. There, she realized there was an untapped market for higher-quality coffee roasted locally. She purchased a Diedrich IR-3, expecting to start a small wholesale roasting shop. But she discovered that she missed working with people—so she shifted gears.

From her years in the espresso industry in Seattle, Crawford still owned a Sonofresco 1-pound roaster and grinders. She decided to integrate a roasting business, which she called Rocky Top Coffee, with an espresso catering business, which she dubbed Latte Elegance Catering. She invested about $10,000 on a catering cart, two new espresso machines, a truck ramp and a website. “It was an inexpensive start up, without the build-out cost of a fixed location, and seemed like an unmet need in the area,” Crawford recalls. She’s now roasting for musicians who play in Nashville, as well as for a premium ice-cream maker in the area, without worrying about how to recoup her initial investment.

2. Roast to learn

For anyone new to coffee, roasting with a smaller machine can be a valuable learning experience. New roasters can learn how beans react during the roasting process and cup the results. And then do it all over again.

“What small-batch roasting afforded me the opportunity to do is to cut my teeth on learning how to roast coffee and living with the mistakes,” says Mary Tellie, founder and CEO of Electric City Roasting Company in Scranton, Penn., who started her business with a single-pound roaster.

For those new to roasting, purchasing a small-batch machine allows operators to get their feet wet and decide whether they truly want to remain on the roasting side of the business—before they make an investment in a larger machine.

“It’s easier to get rid of one pound of coffee than 25 pounds of coffee that’s been baked,” Tellie says. “I think everyone can afford to lose a pound of coffee because it wasn’t roasted right. And so that’s a huge benefit—learning, and trying to focus on profile roasting and understanding what makes this country’s coffee tick. This is assuming that you have absolutely no experience in that at all. How do you find that out? Well, you have to roast some coffee and taste it.”

McGovern considered purchasing a large roaster and afterburner, but when he wasn’t able to secure the start-up capital for the purchase, he decided to go small. He tracked down a refurbished 1-pound San Franciscan sample roaster and opened a coffee cart called Sterling Coffee Roasters in a busy shopping district in Portland. He had no roasting experience, but he and his business partner were keen on experimentation.

“The small roaster gave us a chance to break down the basic components of coffee development and look at that critically because we were doing it every day,” McGovern says. “It’s been a very steep learning curve. We’re learning as we go.”

3. Be versatile

Tellie launched Electric City in 2003 with a single 1-pound Sonofresco roaster. She has since expanded her collection to include four 1-pound Sonofresco roasters, a 1-pound Sonofresco sample roaster, a Probat L-12, as well as half-bag and one-bag Diedrich roasters, and is on track to roast 60,000 pounds of coffee this year. The variety of machines gives Electric City extraordinary flexibility, allowing Tellie to fulfill both small and large orders, roasting just enough for the order without firing up large roasters for tiny batches.

“You can produce a little bit more of a quantity that would be conducive for a larger cupping session with consistency, you can do the same with fulfilling small orders rather than firing up a larger roaster [and] roasting additional coffee you don’t need,” Tellie says. “If I have an order for 4 pounds of the Esmeralda, am I putting that in my 12-kilo? No.”

Cruser Rowland, owner of Jack Mormon Coffee, a roast-to-order retailer in Salt Lake City, cranks up four Sonofresco 1-pound machines on a daily basis. But he also keeps an 8-pound and a 38-pound Sivetz fluid-bed roaster on hand for large batches that he sells at the farmers market or to customers who request several pounds of coffee at once. “I would only [use the 8-pound roaster] in the early morning because I have all day to move the coffee. Unless a customer orders 6 pounds, I wouldn’t fire it up. I would use the [1-pound roasters].”

Similarly, Mersereau decided to stick with small roasters when he retired from his full-time job and turned his focus entirely on Blue Heron Coffee in 2008. He traded in two of his 1-pound roasters, replacing them with two 2-pound roasters. The setup gives Mersereau the flexibility to change the amount of coffee he roasts from day to day, or hour to hour. “I can [roast] as little as 1 pound or as much as 5 pounds at a time,” he says.

4. Watch the bottom line

For roasters who sell 50 pounds or more of coffee every day or two, relying on a single-pound roaster to do the job doesn’t make much financial sense—labor costs will add up quickly, canceling out profits.

McGovern of Portland was already operating an established coffeehouse, so he and his business partner were able to dedicate themselves to Sterling Coffee Roasters without fretting about labor costs for their new venture. “We set out to open the shop and spend the first year roasting continuously on the [1-pound] San Franciscan for very little pay,” McGovern recalls. “So our salaries certainly were not as good as the federal minimum wage. And that helped [the business] a lot.”

Sterling also had a backup plan in case demand eclipsed projections: McGovern and Miller arranged to co-op another business’ 10-kilo roaster. “Within a month and a half, we were … moving some of our espresso volume onto the larger roaster,” McGovern says. “The reason our [business] plan looked good despite the labor was because we had a clear point at which we would begin using a larger roaster in conjunction with the small one. We just didn’t expect it to be so soon.”

Rowland says he prefers the versatility of using single-pound machines to handle his customers’ orders. “It’s like having a giant computer or having several laptops that can do the same work,” he says. “You can kind of dial them in. Say I did 5 pounds of five different coffees and got them out fresh. I don’t have to sit on anything. I don’t want to waste anything or throw anything away.”

As Rowland notes, decreasing waste is a boon to his bottom line. His frugality extends even further—he uses a coffee extractor to create a cold brew from coffee that has been sitting around for more than two days.

5. Buy the best beans you can, and keep them fresh

In many ways, buying quality green coffee for a small roastery is easier than it ever has been. With the availability of microlots and options for direct trade, roasters can get their hands on exceptional coffees. Of course, single-pound roasters won’t qualify for volume discounts, so they should expect to pay a premium for their green beans.

“It’s always harder when you’re the small kid on the block,” says Tellie of Electric City. “Everyone wants to sell a container; everyone wants to sell a pallet. Unless you’re buying a vacuum-packed box or a GrainPro bag or jute bag of coffee, anytime you have to break those bags apart, separate them, and re-sell them, of course you’re going to pay a premium for that. If you are buying 5 pounds of coffee to roast, it’s going to be significantly more expensive than if you bought the bag.”

Purchasing smaller batches of coffee is “astronomically more expensive” than buying in volume, says McGovern. But once Sterling found its suppliers, he took comfort in the fact that he was buying top-notch coffee, despite the extra cost. “In many ways, we were more than happy to pay the extra buck-fifty a pound, green, to buy exceptional coffee,” he says. “It was something that we could count on, meaning, if something was wrong, it was us, not the coffee. We’re starting to appreciate the premium that we have to pay for good coffee, and we attract a kind of audience that doesn’t mind accepting the brunt of that.”

Rowland purchases green coffee by the bag. He stores them at his importers’ warehouses until he accumulates 10 bags (one pallet) to save on shipping costs. Mersereau, on the other hand, saves on shipping by purchasing his coffee as needed from the nearby Sonofresco office.

Though some aged coffees have become highly sought after, many roasters believe that green coffee doesn’t age, it stales. Keeping green coffee fresh is even more relevant when a business is roasting only a few pounds of coffee an hour.

“I don’t necessarily enjoy doing it, but I will pay more money to keep the coffee in Grain Pro packaging in the event that I can’t use it as quickly as I would like to,” Tellie says. “That’s an issue with every roaster, and proper green coffee storage is paramount.”

6. Maintain the machine

Like any roaster, single-pounders need to be properly cleaned and maintained for the best performance. Rowland says his 1-pound roasters are workhorses. “This is our fourth year, and we run them all day, six days a week,” he says.

Rowland has learned to repair his roasters—his most common issue is replacing the igniters—and keeps up a diligent cleaning and maintenance schedule. “If somebody expects to have no maintenance issues, then I don’t know what they’re expecting,” he says. “You have to change the oil in your car.”

The team at Sterling quickly learned about a quirk in their roasting system. Sterling’s single-pounder does not have an afterburner, and the exhaust heats the chaff collector rapidly. As a safety precaution, the Sterling team lets the roaster rest for 10 minutes each hour so it can cool off and collect the chaff. “We didn’t expect that going in,” McGovern says, but “it’s not a fatal flaw.”

Safety comes first when working with any roaster, large or small, notes Tellie. “If you think you’re going to breach a safety protocol, or if you don’t have any kind of roaster maintenance in place, then you should get some quickly,” she says.

7. Entice with single-origins, bet on blends

Single-origin or blend? Often roasters offer both options, giving customers the opportunity to choose between a consistent cup and an ever-changing array of coffees from around the world.

For roasters of any size, it makes good business sense to offer a consistent blend to draw in customers for repeat purchases, says Tellie. While single-origins are Tellie’s passion, “blends keep people coming back.”

Mersereau agrees. He offers 10 different blends in addition to single-origins, all roasted to order in small batches. “I have more people who come to like the blends more than the single-origins,” Mersereau notes.

But some micro-roasters are bucking the blend trend.

With a whopping 50 single-estate coffees on hand, Rowland is passionate about offering new experiences to his customers. When customers request a certain coffee that has run out, he steers them to a similar type of coffee. “That’s part of the fun,” he says. “It’s personalized.”

Sterling also offers a rotating range of single-origins—about 30 different coffees since opening in February 2010—and is experimenting with blends. So far, Sterling has not hit upon a tried-and-true blend; in fact, that’s not the goal. “Essentially, [Sterling] is built around emphasizing how tremendously different coffee is from day to day and season to season,” notes McGovern, “and trying to overcome the natural fear of inconsistency that a lot of people have by emphasizing the quality and service people can expect, even though they may not know what we’re serving or how it’s going to taste exactly.”

8. Don’t be afraid to grow

Starting a roasting business with a single-pound roaster is certainly a safer, less intimidating way to build a business. The start-up costs are minimal—all it requires is the roaster operator’s time.

Mersereau, who roasts about 500 pounds a month on his small-batch machines, says he’s keeping an eye on wholesale opportunities and plans to add to his collection of 2-pound roasters as his business grows. “It’s probably a little more of an investment doing it that way,” he says, but he likes their ease of use. “I’m doing all of the roasting myself, so I know the levels that I want to roast the coffee to. It’s really easy to get what you want without messing around.”

If a business continues to sell increasing amounts of coffee, however, it may be difficult to keep up with demand without hiring help and investing in a larger machine.

“You can get into roasting coffee and start selling your coffee with a small roaster for not a lot [of money],” Tellie says. “Does that mean you have a profit margin? You’re probably going to up front, but I think it’s going to be the law of diminishing returns. After a while, you’re no longer [profitable] because it’s not efficient.”

Tellie said the biggest mistake she made was not investing in larger roasting equipment from the start. “Going bigger, you’re not going to be as profitable up front,” she says. “But if you’re that good at what you do, then you don’t have to worry about it going forward. Your growth will already be built in, versus having to redo a roastery.”

In many ways, these micro-roasters have embraced the flexibility of using larger roasters to handle growth. Electric City roasts about 80 percent of its coffee on its larger roasters, while Sterling roasts 60 to 70 percent on its 10-kilo machine and Jack Mormon uses its Sivetz fluid-beds to roast about 40 percent of its beans. But all three of these businesses also hang onto their single-pound roasters for smaller orders.

The next level

It’s clear that small roasters offer a way to break into the coffee industry at a minimal cost and give businesses the flexibility to roast in small increments as needed.

“If you didn’t have the small-batch roasters, you wouldn’t have a lot of the middle-size roasters you have today,” Tellie says. “I think that they started small and they were able to grow.

“Every company’s going to find their own way.”

Mark Crawford is director of business development for Mont Blanc Gourmet and, when home, enjoys his morning espresso macchiato crafted by his wife, Charlotte Crawford. He can be reached at mark@montblancgourmet.com.